A Conversation with Four Former Missionary Kids

The Joys, Challenges, and Lifelong Impact of Growing Up Overseas

“My worst grade in college was U.S. history,” said former missionary kid Rebecca Elder. “I remember one time my professor mentioned Jamestown. I turned to my friend and asked, ‘What’s Jamestown?’”

Her friend laughed until she realized Rebecca was serious. “I had to remind her that I’m not from here,” laughed Rebecca.

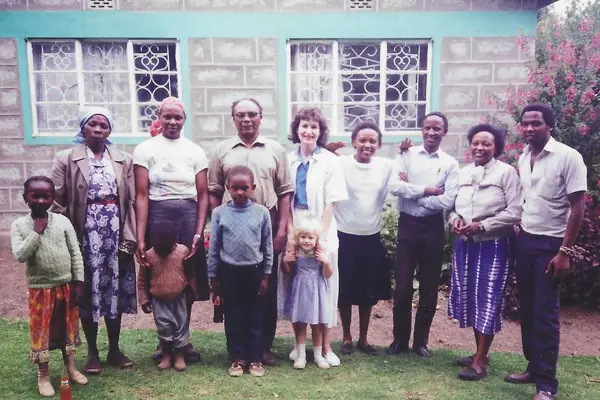

Rebecca grew up in Africa where her parents served as MTW missionaries in Kenya and South Africa. When she was 18, she moved to the U.S. to attend Covenant College. Unlike most of her classmates, she did not have 13 years of U.S. history classes under her belt.

This humorous story is one of many Rebecca and three other adult MKs recently shared about their experience as third culture kids. From their adventurous cross-cultural childhoods to repatriating to the U.S., they recount the joys, the challenges, and lifelong impact of growing up overseas.

They enjoyed their cross-cultural childhood.

“There is nothing that I can possibly imagine that is equivalent to experiencing a completely different culture as a young child,” says Lydia Young. “Your brain, your heart, and the way you see the world will never be the same and I’m so thankful for that.”

Lydia’s family moved to a suburb of Tokyo when she was 5 and she loved everything about the two years her family spent serving in Japan. Having moved from downtown Philadelphia to one of the cleanest, safest cities in the world, Tokyo gave Lydia and her siblings the freedom to explore without fear of harm. She remembers outings such as putting on her roller skates, riding the train, and roaming the zoo all day with other children without any adult supervision.

Lydia’s husband, John, was born and raised in Tokyo where his parents served as MTW missionaries. He echoed his wife’s thoughts saying, “I was given the freedom … to just go out into the world all by myself and do whatever I wanted. Like ride my bike or go find some woods to wander around in. It was very safe … Japan’s a smaller place, too, so everything’s a bit more accessible.”

Rebecca has similar sentiments about growing up in Kenya. “I loved my childhood,” she says. It was a time of wonder, play, and wildlife. She spent her days searching for chameleons and monkeys and climbing trees. Once she even watched a lion eat a zebra.

In the same vein, Seth Iverson, who was also born in Japan to MTW Tokyo missionaries, liked how missionary life made the world more available.

“I think in some ways the world feels a lot smaller when you’re growing up on the [mission] field … in the sense that you can kind of go anywhere and see anywhere,” says Seth.

Missionary kids grow up traveling to new places, eating good food, and meeting different types of people—all leading to an adventurous childhood full of opportunities to experience the beauty, diversity, and complexity of God’s great, big, wonderful world.

They are thankful for an expanded worldview.

With the world seemingly at their fingertips and a childhood full of cross-cultural experiences, it’s no wonder that MKs develop an expanded worldview. This is one of the aspects of growing up on the field that the MKs interviewed are most thankful for. It has benefited the way they interpret, process, and view people, this world, and their lives.

First, it means their natural disposition toward others is one of understanding and grace—especially for the foreigner, outcast, and marginalized. Giving the benefit of the doubt is instinctual to them because they know people have different perspectives and backgrounds.

This is especially true for people from other cultures. MKs have firsthand experience of what it feels like to be an outsider and are always aware of the ethnic minorities among them. They are drawn to them, move toward them, and are comfortable building relationships with them.

Practically speaking, globalization has made the ability to work with and relate to people from different places a necessity. Seth commented on this saying, “I work as a practice manager at a clinic … and most of the team that I lead are people from all across the world. Having that cross-cultural context means that even if I don’t know their culture, I know to ask about their culture and I know there are going to be cultural differences. I’m not thrown off by that.”

He continues, “Nowadays there are people from all over the world everywhere. And it’s a very useful skill and something that I really enjoyed about my upbringing.”

Having compassion for people different from them also means MKs are equipped and motivated to answer God’s command to care for the poor and vulnerable.

“If you never put yourself into being in a minority situation, you can’t appreciate the minorities in America or anywhere,” says John. “The Bible just talks so much about the outcast and the poor and how blessed those people are. And while that stuff was extremely hard to go through at the time, I definitely wouldn’t trade it. [The experience of living as a minority] made me not only capable of dealing with it myself, but gave me a visceral appreciation for others going through it in my ability to feel their pain alongside them.”

Second, this expanded worldview means MKs have a global view of the church and a big view of God. For example, when Seth thinks of the Church, he thinks diversity. It doesn’t take any effort for him to picture people worshipping God from every country.

“Growing up as a TCK and then also having parents who are missionaries, they were … always framing things in terms of multiple [cultures],” said Seth. “I really do think our [MKs’] view of God, and how He is worshipped, and how He will be worshipped one day in heaven is with all peoples from every tongue and tribe. … It’s going to be from all over the world … and that mindset was just part of my upbringing.”

Similarly, Rebecca says, “With this big view of the world, you realize the Church looks different in other countries. And that’s good and beautiful,” she says.

A big view of the Church and of the world naturally leads to a deeper understanding of God as the creator, ruler, and redeemer of the world. MKs have an appreciation for both God’s transcendence and His immanence.

Rebecca expressed this perfectly, saying, “God’s involved in the whole world and is doing so many things that I don’t even know about. There’s just this awe of Him that has developed from realizing all of that. And with it, too, just how big and good He is. He is involved intimately in my little life and then this huge world and in the little lives in the world.”

They struggle with their identity, sense of home, and feeling like they don’t belong anywhere.

Most TCK literature says one of the main difficulties of the globally mobile upbringing is feeling rootless. Lydia and Rebecca confirmed the reality of this challenge. According to Rebecca, it stemmed from looking American but not feeling American. And while she has found her place in the U.S., the internal tension lingers in adulthood.

“Sometimes I tell people I’m American, but I definitely feel like my heart is in Africa and I still have both feet in different worlds,” says Rebecca. “It’s still weird. I feel like I belong, but I also still feel like a nomad.”

Lydia shares Rebecca’s thoughts, saying, “When you love two places, you’re never really all the way happy in one again and that’s a tough place to be.”

While this sense of homelessness inevitably led to seasons of loneliness, feeling disconnected, and wrestling with their identities, Rebecca and Lydia said that this struggle positively impacted their faith. It removed the temptation to put their satisfaction and security in this world.

“I don’t think it’s a bad thing. This world is not our home and nothing demonstrates that quite as well as never really feeling like you fit,” says Lydia. “I think in a way, it was helpful for me in becoming a believer that I was always asking myself, ‘What am I looking for?’ And it was easy for me to recognize the answer is not ‘good friends.’ The answer isn’t academic performance. It’s not your family. Our hearts are restless until we find our home in Jesus and in my opinion, I came to that earlier in life than I might have otherwise.”

Rebecca has a similar perspective on the value of growing up as a believer. “I’ve loved that with the hardships of being a TCK and struggling with the questions, ‘Where is my belonging? Where is my home?,’ all of those answers are in the Lord and He’s right there with me when I wrestle through them.”

Their upbringing was full of transitions and repatriation was one of the hardest.

While adventurous and exciting, the TCK life is also a never-ending series of transitions. There are positives and negatives from this childhood of constant change. TCKs are adaptable, flexible, and comfortable living outside of their comfort zone. They can competently handle unfamiliar situations. But their upbringing can also lead to a need for change and unprocessed grief because of the revolving door of friends, family, and places.

Of all the transitions, the four MKs interviewed said that repatriation—moving to the United States for school—was one of the hardest. TCK resources agree.

Seth remembers his brother, Mark, taking him to get a milkshake at Cookout the week after he moved to the U.S. to attend the University of Virginia. On the way there, Mark excitedly told Seth about Cookout’s 48 mix-and-match milkshake flavors.

“That sounded so overwhelming,” says Seth. “We go into this place and I ordered a plain vanilla milkshake.

“The cashier stops what he is doing, looks up at me and says, ‘You’re just going to get a vanilla milkshake?’

“Then the guy behind me in line says, ‘Dude, you can’t just get a vanilla milkshake. There’s so many options.’

“Then the guy behind him shouts, ‘You can’t take that from this guy. Tell him we’re not going to stand for that.’

“That was one of my first interactions. Coming from Japan where no one will share with you their opinion about anything and coming here where everyone shares their opinion about everything, unsolicited, was very, very different.”

When repatriating to the U.S., MKs experience the same level of culture shock as anyone would moving to a different country. But since many of them look American, people don’t always realize they struggle with cultural adjustment.

Specific repatriation challenges John, Lydia, Rebecca, and Seth mentioned are the overwhelming number of options in the U.S., American materialism, adjusting to the weather, driving, pumping your own gas, not understanding pop culture references, feeling misunderstood by peers, and the nominal Christianity that pervades the American evangelical church. For many of them, it took years to make close friends.

“Forming friendships was hard—just not having immediate cultural context and being confused as to why everyone talks about sports all the time,” says Seth. “It definitely took a while for me to feel like I was tracking with what was going on.”

Unfortunately, there isn’t a way to eliminate the difficulty of repatriation, but there are ways to smooth the transition. Rebecca mentioned that growing up her parents made sure she was familiar with American culture so that she wasn’t completely blindsided. She and Lydia also said that connecting with other MKs, helped them find people who understood them. John and Lydia both found solace in God’s creation.

“The natural world has been such a huge encouragement to me. … It feeds your soul. It feeds your psyche and I can’t overstate what that meant to me when I came back and went to boarding school at McCallie High School,” says John. “I got involved in the student outdoor leadership program and it was huge. I got to rock climb for the first time, and we’d kayak and go on backpacking trips. It was something that I had already missed a lot of growing up in Tokyo and that did wonders for my brain. It’s such a simple thing … but we probably don’t give enough credit to God’s creation.”

Lydia adds, “I think God speaks so strongly through creation. He did in my life and my first experience learning to pray and communicate with God were on my horse in the woods and I’m so thankful for that. I’m so thankful for space and time … and I always tell people sunshine and exercise are the best medicine you can get.”

Advice for missionary parents.

As John, Lydia, Rebecca, and Seth reflected on their upbringing, they had thoughts on how missionary parents can help their kids thrive as TCKs.

First, it is important to stay informed. Rebecca said that there weren’t a lot of resources on TCKs when she was growing up, but she knows her parents sought out those that did exist and implemented the advice. They also taught her about the unique TCK experience, which equipped her to navigate growing up between cultures and know which parts were going to be hard. One of the most important things her parents did was help her have closure whenever it was time to leave.

“Find out what your child loves and will miss and be intentional in helping them say goodbye. This includes saying goodbye to places, foods, and activities. Things that we did to say goodbye included taking pictures, making memories with those things and at those locations, intentionally saying goodbye—verbally or just mentally—buying little trinkets to remember a place by, and making a photo album,” says Rebecca.

Lydia advises parents, especially itinerating missionary parents, to avoid sugarcoating things. “Don’t just point out this is going to be great and say, ‘These things are going to be fun. You’re going to be fine. You’re going to make new friends,’” says Lydia. “It’s hard. There are a lot of emotions and especially for young children who don’t understand things like grief or social anxiety.”

She and John say it is important to allow your children to feel what they feel and to make yourself emotionally available to them. This is going to take some effort. Parents may have every intention of giving their attention to their kids but the pressures of support-raising, international moves, cultural adjustment, and ministry demands often leave parents with limited emotional capacity. Knowing that their parents are stressed can also prevent kids from voicing their feelings or struggles out of fear of adding to the burden.

Finally, and by far most importantly, the four adult MKs encourage parents to build safe and healthy relationships with their kids.

“I think it really starts with a good relationship that you have with your children so that you are already able to talk with them about the hard things that they’re going through. That’s going to be the most helpful thing for them when you move overseas,” says John.

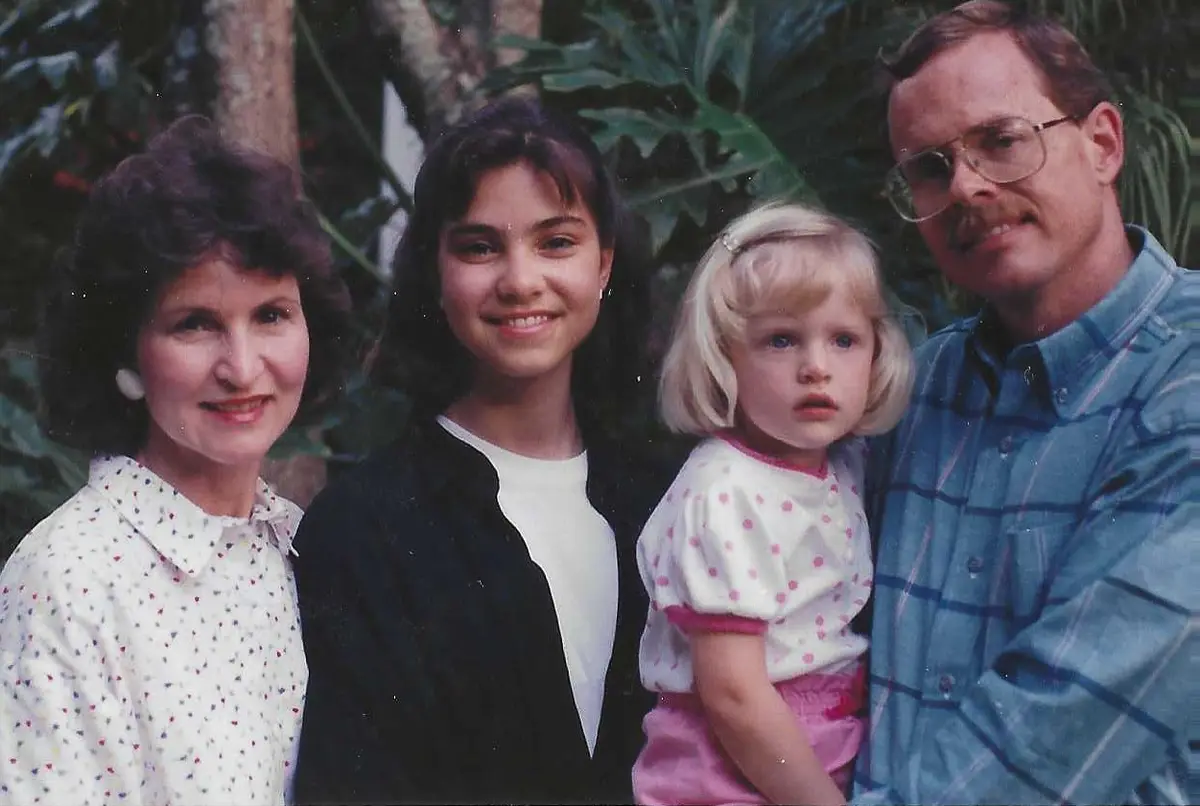

“A big thing that helped me was having a strong family unit that felt safe and stable,” says Rebecca. “Actually, my sense of home has always been my family and not location-focused—which I think is a TCK thing. No matter how unfamiliar and confusing the place and season I was in at the time, and how much I felt like I didn’t know where I belonged, I knew I could go to my family, that I belonged to them and that I was known, supported, and loved.”

Seth and John emphasized how important it is to maintain a strong family dynamic while serving on the field, especially when it comes to a wise work-life balance. There are so many demands when serving internationally, so that balance may not look the way it does in America—but it is still important.

“If you don’t set up boundaries as a family, your family suffers for it,” says Seth. “One thing I loved that my family did is we had a place we went to rest in the mountains of Japan … Every single one of my [8] siblings looks at that place with such fond memories. It just equates itself with rest and peace. … Especially if you’re serving long term somewhere, make it a tradition to go somewhere to recharge and recuperate.”

“I think encouraging parents to not be workaholics and to have time for the family is not only good for your kids but it’s good for your ministry,” says John. “People need work-life balance and that’s the truest in Japan. Japanese people are literally the hardest working people in the world and Americans are kind of similar … If we could show a model of being available to our children and valuing time with our children, it would not only help our kids but it would help our witness as well.”

The Good News for Parents and MKs

The good news for missionary parents and future MKs is that John, Lydia, Rebecca, and Seth all had a positive experience. Each said they wouldn’t trade the difficult parts because God used them to shape their faith, develop their ability to process the brokenness of the world, and increase their empathy for other people. Each of them would do it all over again.

TCK Resources for Missionary Parents

Websites and Blogs

TCK Training

Tanya Crossman

A Life Overseas

Michele Phoenix

Interaction International

Kaleidoscope

Books

Tarmac: A 10-Week Guide to Making Sense of Your Multicultural Story by Laura Ward and Brenda Keck

Third Culture Kids 3rd Edition: Growing Up Among Worlds by David C. Pollock, Ruth E. Van Reken, and Michael V. Pollock

Misunderstood: The Impact of Growing Up Overseas in the 21st Century by Tanya Crossman

Setting Sail!: The Family Workbook by Dr. Emily G. Harvey

Raising Resilient MKs: Resources for Caregivers, Parents, and Teachers by Joyce M. Bowers (editor)

Belonging Everywhere and Nowhere: Insights into Counseling the Globally Mobile by Lois J. Bushong

Raising Global Nomads: Parenting Abroad in an On-Demand World by Robin Pascoe